Names are important. When we give names to our children we think deeply about both our past, and the uncertain future into which the name we give them will bear them. My parents gave me what became my professional name, Christopher, which means ‘bearer of Christ’ – and it might surprise you to learn how often it is incorrectly abbreviated to the spelling ‘C-h-r-i-s-t.’ I’m addressed that way in E-mails all the time, and also have seen myself so-called on posters, newspaper ads, even once on a flashing marquee sign! A comment on the intersection of auto-correct and spell-check with our general lack of personal time to put the care needed into the things we type and print!

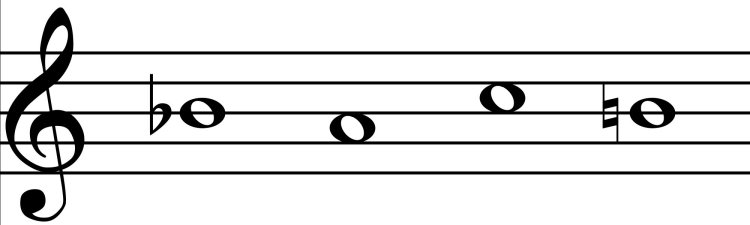

So, spelling matters! Johann Sebastian Bach was by no means the first composer to realise that alphabetic note names like A,B,C,D,E,F and G could be used to spell things, but he famously included his ‘signature,’ the letters B-A-C-H in his final composition “The Art of Fugue.” (Incidentally, by an accident of history, in German the note we call B-natural is called ‘H,’ while the note we call B-flat is ‘B.’

His example inspired composers like Robert Schumann, Franz Liszt, Max Reger and others to write their own compositions based on B-A-C-H in tribute to the great Master – and later it inspired other composers to do the same using the spelling of the names of other tributees. Such is the case in our program’s opening piece, Québec-born composer Denis Bédard’s tribute to his organ teacher Claude LAVOIE, written in 1994 as the test piece for the Québec Organ Competition. The Rhapsodie is a free set of variations on the six letters of Lavoie’s name wrapped in a grand introduction and finale.

Now I will mention another name: Jéhan Alain (1911-1940). He was a skilled motorcyclist, and became a dispatch rider in the Eighth Motorised Armour Division of the French Army. On 20 June 1940, he was assigned to reconnoiter the German advance on the eastern side of Saumur, and encountered a group of German soldiers at Le Petit-Puy. Coming around a curve, and hearing the approaching tread of the Germans, he abandoned his motorcycle. After using his machine gun to shoot several infantry soldiers who had ordered him to surrender, he was himself killed at the age of 29. What would become known as the Battle of Saumur can be seen as the beginning of what became the French Resistance, as Vishy France collaborated with the Nazis and the rest of the country was quickly overrun. Men and women like Jéhan Alain cared enough to make to resist the enemy both without and within their lands, and in cases, to make the supreme sacrifice.

Alain is not remembered today mainly as a martyr for France – France had plenty of those mid-century, by the end of two world wars. Today he is remembered for something much more rare, as one of the most individual creative minds at work in the incredibly productive French music scene of the 20th century’s third and fourth decades. The musical output of his short life represents a remarkable fusion of the sacred and secular traditions that formed him, and also a uniquely French incarnation of the ‘striving artist’ so famously birthed to the world a century before his birth in figures like Goethe and Beethoven.

His Trois Pièces pour Orgue are today his best known works – each is variations on a single melodic idea – and each also suggests a very human idea:

1) homage to history by reimagining, in his own unique way, a melody from his 16th century countryman-predecessor Clément Jannequin,

2) refuge for the artist within the ‘hanging garden’ idea made popular in colonial Europe by the ‘Hanging Gardens’ of Babylon (one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World already forever gone by Alain’s time), and

3) faith in suffering – a testament to the universal, but perhaps most keenly Catholic power of repetitive prayer while facing the trials of life. Alain wrote “When the Christian soul in distress can no longer find the words to implore God’s mercy, it repeats incessantly the same invocation with a vehement faith. Reason has attained its limit, only faith can pursue salvation.”

Alain and any future compositions he might have produced were lost to us that day in June 1940 – but thanks mainly to his younger siblings Olivier and Marie-Claire Alain (both also distinguished musicians) much of his music is preserved. What I want us to think about is not so much that music, which I think will speak for itself – but rather his service to his country, that brought to an end his short life. As our world continues to elevate tyrants and despots to lead its countries, including in such unexpected places as our southern neighbour, Alain’s example speaks to our moment.

Maurice Duruflé (1902-1986) wrote his Prélude et Fugue sur le nom d’Alain in 1942, two years after his younger colleague’s death. It is a spiritual descendent of the Germanic compositions mentioned above that monument the great Bach through that literal-typographic lens, but as you will hear its Prélude also touchingly quotes the melody and harmony from Alain’s best-known composition, Litanies, which you heard a few moments ago.

Our program today concludes quietly with one of Alain’s final compositions, a Prelude for the Office of Compline, which I have added today because our afternoon together here at St Andrew’s will conclude with Evensong. Though well known in the Anglican church, the idea of ‘Evensong’ is not familiar to many of us – it is a 16th century English condensation of the evening services of Vespers and Compline the Roman Catholic monastic tradition of the Daily Office… the comparable evening worship service in which is Compline.

—–

Rhapsodie sur le nom de LAVOIE – Denis Bédard (b. 1950)

Trois Pièces pour Orgue – Jéhan Alain (1911-1940)

– Variations sur un thème de Clément Janequin

– Le Jardin Suspendu

– Litanies

Prélude et Fugue sur le nom d’Alain – Maurice Duruflé (1902-1986)

Postlude pour l’office de Complies – Jéhan Alain (1911-1940)

Leave a comment